Tarantula “Tuesday”: Metallic Pink Toe

I know this isn’t the normal Tarantula Tuesday post (mainly because it’s Thursday), but I can’t leave you all without another tarantula species right? So this week, we will talk about the metallic pink toe (Avicularia metallica).

Tarantulas in the genus Avicularia are arboreal, meaning that they spend the majority of their time living in the trees. They are fantastic climbers and can climb up glass without a problem. There is always a risk of falling, but arboreal tarantulas lose their grip less frequently and seem to be more resistant to falls than their terrestrial counterparts.

Avics are generally considered to be a good beginner arboreal tarantula and the A. metallica and A. avicularia are both pretty easy to find. Care is a bit more difficult than other beginner species (such as the Brachypelma that I highlighted over the last two weeks), but it is still a fairly easy tarantula to keep.

To start things off, you need an enclosure with more height than floor space, so your Avic can climb around to its little open heart’s content. I personally keep mine in a snack container that I got for a couple dollars from Walmart (kind of like these). Once they have that space, you can decorate with cork bark, branches, really just about anything, as long as it’s clean. You can also choose to put nothing in and your Avic will web it’s own home onto a wall.

Avics usually tolerate handling well, though they can be a bit skittish. Biting is rare since they would rather just flee. But one thing that they commonly do is shoot their frass (fancy entomology word for poop). My A. metallica has quite the range and can fire frass well over a foot. She does that every time I get her out, but quickly calms down and just wanders.

To care for Avics, you have to keep two things in mind: humidity has to be kept fairly high (~70-80%) and good ventilation is an absolute must have. If there isn’t good ventilation, then the stagnant air in the enclosure will eventually suffocate your tarantula or cause mold to grow in its book lungs. They do like it on the warmer side, with temperatures in the mid-70s to mid-80s being ideal, but not necessary.

More info about the A. metallica and other Avics can be found here

References:

“Tarantula and Scorpion Handler’s Blog: Avicularia Tarantula Caresheet.” Tarantula and Scorpion Handler’s Blog: Avicularia Tarantula Caresheet. N.p., 31 Mar. 2011. Web. <http://tarantula-and-scorpion-handlers-blog.blogspot.com/2011/03/avicularia-tarantula-caresheet.html>.

Schultz, Stanley A., and Marguerite J. Schultz. The Tarantula Keeper’s Guide. Hauppauge, NY: Barron’s Educational Series, 1998. Print.

The Arrival

I’m a bit behind on this post, but I couldn’t resist. While my posts have been pretty focused on tarantulas right now, I can mix it up with a cool post about beetles.

Breaking open rotting logs in forested areas is a favorite past-time of mine. You never really know what you will find. Something that is in almost every log is beetle larvae. A variety of larvae can be found, from click beetle to stag beetle. I’ve tried casually keeping larvae I’ve found before, but my success rate has been pretty low (with flat bark beetles being my only real success). But then I came across a forum for beetles, where people keep native and exotic beetles and beetle larvae. The clincher was when I got my beetle breeding and rearing book (seen in “In Pursuit For Knowledge“). The book proved to be an extremely good read and I learned an unbelievable amount about keeping beetles and beetle larvae.

But after reading and reading and reading, I was finally ready to take the plunge into serious beetle keeping (cue dramatic music). Now a very glaring question arises. Where the heck do I get adult beetles or larvae? Certain families can be readily found around here, but after several previous attempts with smaller species, I wanted to start off with a bang. I scoured beetleforum.net until I came across an interesting species that was considered to be a good beginning species. Sounds good right? I figured I would get a couple larvae, rear them out, and get some decent sized beetles that I would breed and sell the larvae off. But after I bought the larvae and they arrived, I was in for quite the surprise.

These larvae were massive. To be honest, I really didn’t know what to expect, but it wasn’t something this large! I was extremely excited and quickly placed the sexed larvae (that’s right, you can sex them before adulthood as long as they are final instar) into a large enclosure with more than enough rotting wood for them to feast on after their long(ish) journey.

Shipping larvae is pretty sweet. You just place them in a cup of some sort with substrate/food, put some padding in the box and around the cups and send them off. And let me tell you, the guy who sent them to me did a heck of a job with the packing. It’s cold here, but priority shipping is always and option with beetle larvae. They don’t have to be shipped express, so that saves you some money right off the bat, and you get to recycle those pesky old deli cups!

Oh, I forgot to mention what species I’m keeping? Silly me. They may not look particularly exciting now (besides the whole massive part), but in a few months they will. My first beetle species to keep is…Allomyrina dichotoma, aka, the Samurai helmet beetle!

For more information on A. dichotoma, check out these links:

http://carnivoraforum.com/topic/9680884/1/

https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.435138719898779.102520.430512957028022&type=3

I’m really hoping to get lucky with theses guys and get some breeding adults. I would only have one male and one female, but you gotta start somewhere, right?

Tarantula Tuesday: The Mexican Golden Red Rump

This week we will keep with the Brachypelma them and talk about the Mexican golden red rump (Brachypelma albiceps).

B. albiceps are kept just like last week’s tarantula, the Mexican red knee (B. smithi). Humidity should be kept low, a water dish and hide should be provided, and feed once every couple weeks.

My female is very docile and a good eater. She is very active when brought out for handling and does not get startled easily. For an experiment of sorts, I’ve placed a ping pong ball in her enclosure and have seen her rolling it around from time to time. I’m not sure if she thinks it is an egg sac, or just enjoys reorganizing her enclosure by moving the ball around. Either way, it has proved entertaining.

If you get a chance, I fully recommend getting this tarantula. They aren’t easy to come by in the U.S., but other arachnophiles have begun breeding them. I will help with breeding as well, once I come by a male at a good price. Hopefully their numbers will be higher in the future, which will drop the price.

A full caresheet can be found here:

http://www.mikebasictarantula.com/B-albicep-care-sheet.html

References:

Schultz, Stanley A., and Marguerite J. Schultz. The Tarantula Keeper’s Guide. Hauppauge, NY: Barron’s Educational Series, 1998. Print.

Tarantula Tuesday: The Mexican Red-Knee

For the first highlighted species, I’m going to talk about a hobby classic, the Mexican red-knee (Brachypelma smithi).

The Mexican red-knee is an iconic tarantula, recognized by many and considered to be the stereotypical tarantula. It has even been used in old movies, such as Tarantula. This beautiful species is highly sought after due to its docile nature, bright colors, and hardiness. Care is simple because the red-knee doesn’t need a high humidity and can tolerate long periods with little/no food or water. The hardiness comes from being a desert dwelling terrestrial tarantula. Red-knees are found on the west coast of Mexico.

While only found in a couple small areas of Mexico, this species has been captive bred for years, much to the delight of arachnophiliacs such as myself. B. smithi‘s being captive bred drops the price and causes less environmental stress because fewer individuals are being wild-caught and shipped throughout the world. And as an added bonus, people can now have a tiny red-knee spiderling that they can watch grow, sometimes even starting from 1/4 inch (0.6 cm)! They can live for a long time, with B. smithi females living for over 20 years quite easily. Males are not as long lived, dying a few months after they molt into maturity, which usually only takes around five years.

In terms of care, B. smithi‘s are extremely simple to keep. As a terrestrial tarantula, floor space is much more important than height. In fact, less height is a good thing because there is a smaller chance that the tarantula will fall and injure itself. Fall are dangerous for a tarantula. Even a fall of a few inches could be deadly (assuming it’s a terrestrial species. Arboreal species can take falls better).

All that this tarantula needs is a couple inches of substrate to burrow into and rearrange as it pleases, a hide of some sort (could be a piece of corkbark, a flower pot, tupperware container, etc.), and a shallow water dish. That’s it. Humidity doesn’t need to be high, with around 50% being acceptable. I personally mist mine once every week or two and make sure that the water dish stays full.

This beautiful tarantula is a treat to keep, and I recommend them to anyone and everyone who loves tarantulas.

References:

“Brachypelma Smithi.” Brachypelma Smithi. Web. 19 Nov. 2013. <http://www.mantid.nl/tarantula/smithi.html>.

Deakin, Billy. “Brachypelma Smithi – Mexican Redknee Tarantula Caresheet.” Tarantula Care. N.p., 2012. Web. 19 Nov. 2013. <http://tarantula-care.com/brachypelma-smithi-mexican-redknee-tarantula/>.

Schultz, Stanley A., and Marguerite J. Schultz. The Tarantula Keeper’s Guide. Hauppauge, NY: Barron’s Educational Series, 1998. Print.

In Pursuit of Knowledge

While I seem to greatly focus on tarantulas, I have other arachnological and entomological passions. Due to the impending winter (cue sad string music), my posts on insects may become a bit more sparse. Or will they??

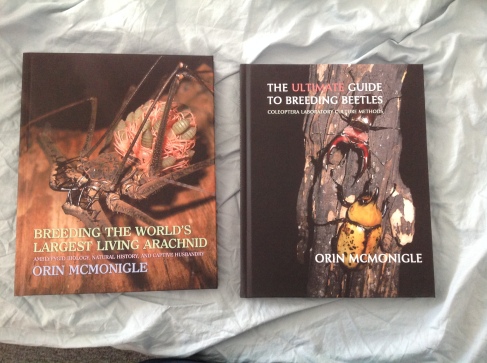

I recently got two books in the mail. They are both proving to be good reads thus far and both are fairly recent, so there haven’t been many major changes (yet).

That’s right. I’m going to be getting into breeding arthropods other than tarantulas. The amblypygids, a.k.a. tailless whip scorpions or whip spiders, will be put on the back-burner for now until I get more space and find a mate for the one have now (and figure out how the heck to sex juveniles/sub-adults…). The variety of that order is astounding and I am very much looking forward to that in the future.

My main project will be learning how to breed and rear beetles. I currently have a couple larvae sitting in nice cups of substrate, so I’m playing the waiting game on those. What I’m excited for though, is the new additions that I will likely be coming in next week. I’m getting a sexed pair of samurai helmet beetle (Allomyrina dichotoma) L3 larvae!

L3 means that the larvae is in its third instar, or it has molted twice since hatching out of the egg. Most, if not all, beetle larvae have three instars before they pupate and then eventually emerge as adults. Some species will remain larvae for months or even years (ex. some cerambycids and dynastids). A story that a professor of mine told was about a cerambycid (long horn beetle) larva that remained in a bookcase for decades before it finally emerged one day, giving the family who owned the bookcase quite the shock!

I’ve always been interested in keeping beetles, so this is a fun first step. I’m planning to expand my range next year and collect several harder to find species, along with becoming a bit more specific in what I collect. The only way to start that though is to read, read, read, and for fun, read even more. But it’s winter here, so I’ve got a lot of time on my hands.

Tarantula Tuesday: A Little Biology

Tarantulas are generally considered to be hairy, eight-legged behemoths that exist only in the tropical habitats (or people’s nightmares). But this is not the case! They are hardy creatures that are able to survive in a variety of habitats, from cloud forest to desert. We even have several species here in the United States, though they are mainly found in the Southwest.

To get Tarantula Tuesdays started off, I’ll give a bit of background on the biology of tarantulas, and next week I’ll start highlighting species. Tarantulas are arachnids, though not physically the largest (see here, with pics of one of the largest species being seen here). Some species do get very large though, with the Goliath bird eater (Theraphosa blondi) breaking 12 inches (30.5 cm) pretty easily. On the other end of the size spectrum though, are dwarf tarantulas, with species like the Trinidad dwarf tigerrump (Cyriocosmus elegans) stretching out to around 2 inches (5 cm).

A question I get a lot from people is “How poisonous are they?”. First off, tarantulas are venomous, not poisonous. The difference between those terms is that in order for something to be venomous, it has to actively inject the toxin into you (ex. spiders, snakes, scorpions). For something to be poisonous, you have to ingest it or come in contact with it (ex. mushrooms, some caterpillars). While tarantulas are venomous, it is generally not something that has to be worried about. Most people equate tarantula venom to bee venom (except in Old World species, which I will get into at a later date).

Since venom is biologically expensive to make, tarantulas do not like to use it unless they have to. Many species would rather kick off urticating hairs instead. Urticating hairs, when looked at under a microscope, look like this.

These hairs are built to irritate and boy, do they. I have gotten haired a couple times and it is uncomfortable. But it is not something that the tarantula will normally do unless disturbed. Many species will even try to run away first, but if their assailant keeps it up, the tarantula will start kicking hairs off. The video here shows a tarantula kicking off some hairs when disturbed (Notes: Handle tarantulas at your own risk! Also, I do not agree with the method of whoever made this video to get the tarantula to kick). The severity of the itching varies from species to species, though I have heard many people say that the hairs from a Goliath bird eater (T. blondi) are the worst.

Don’t worry, I’m not going to skip out on reproduction. That will be a post all in itself I think, since there is a lot to it, and because I’m waiting to see how things turn out with my first breeding project.

Citations:

“Tarantula Biology.” Tarantula Biology. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 Nov. 2013.

Schultz, Stanley A., and Marguerite J. Schultz. The Tarantula Keeper’s Guide. Hauppauge, NY: Barron’s Educational Series, 1998. Print.

Warm Weekends of November

The warmer weekends in November are always such a treat. The sun is shining, the insects are out about (heck yeah!), and I was able to get out to a nearby park to do some dragging for ticks. That’s right. Dragging for ticks. The black-legged tick (Ixodes scapularis) to be precise. This little tick is actually what I’m spending my Master’s thesis working on.

Instead of going to Chicago to visit my field sites, I opted for a more relaxing weekend by dragging at a nearby park that badly needed some exploration (though of course I forgot my camera). The day was perfect and the drive to Kickapoo State Park could not have been better. The winding roads and colorful trees were beautifully peaceful.

I really only dragged at one spot, but it was a spot to remember. To start things off, I went into the woods next to a playground where several small children were playing. Needless to say, they all stopped and stared at me, slightly fearful I’m sure of the strange man walking into the woods wearing a white tick suit and carrying a drag cloth.

Undaunted, I marched into the woods, unrolled the cloth, and started dragging for ticks. It was not long though, before I got distracted and started hunting around for insects. I used some fallen branched to beat trees (no luck) and whenever I checked my drag cloth, I would look at the other creatures that got picked up as well.

Persistence finally paid off though and I got some ticks! I came away with five I. scapularis: one male and four females, though one I will need to look at under a microscope to confirm. But my luck did not stop there. Oh no, I came across some deer scat as well. I took a small twig and poked around a bit, finally coming across what I was looking for.

Recently, I’ve developed a fascination in dung beetles (though not at the same level as other beetle families), so I was hoping to maybe find some under the deer scat, despite it being late in the season. And my luck held out. I found a small species that was undoubtedly a dung beetle. Overjoyed, I poked around a bit more and captured two others as well. If I am lucky, I will get them identified to genus this next week, so I’ll update this post if I figure them out.

Overall, it was a successful day and a beautiful weekend. I am hoping to get a few more days like that before the snows come and central Illinois gets covered with a blanket of white.

What It’s All About

Nature is a passion of mine, but entomology holds a special place in my heart. This is why I’m pursuing a degree in it. In this blog, I want to be able to post thoughts/stories/information about anything nature or entomology related (which you’ll find usually go together quite well). My goal is to post weekly, but it may happen more often, depending on what’s happening (Tarantula Tuesdays sounds like it could be fun…).

I hope you, the reader, enjoy it!

The Switch Over

I was originally posting from a blog call Notice Nature (http://noticenature.blogspot.com/), but the title and the feel just weren’t right, so I’m going to try again here on WordPress with a new title and a new mindset. We’ll see how it goes!